a. natasha joukovsky

journal

AN ENGLISH MAJOR-TURNED-CONSULTANT'S GUIDE TO RIGHT NOW

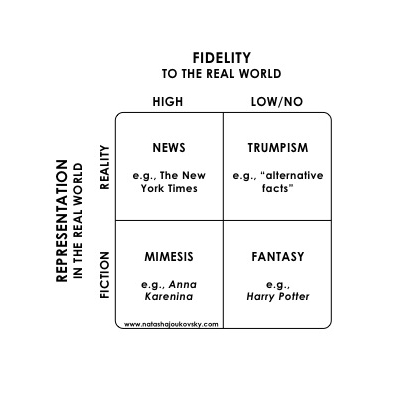

For anyone who has been having trouble keeping things straight recently.

Alternate title: Dear President Trump Please Stop Offending Not Just Reality But Also Actual Fiction

Made this for anyone who has been having trouble keeping things straight recently. As a human being, I'm offended by his assault on facts. As someone in the process of writing a novel, I'm offended by the bad name he is giving to fiction.

SELLING ANTI-CONSUMERISM

Increasingly, we see companies and individuals selling us the absence of things, selling us on negative space, on minimalism. How do you sell things when consumerism itself is passé? You sell anti-consumerism.

Full-page Patagonia ad in the New York Times published black friday, 2011.

As a subjective but real yearning for a persuasive illusion, glamour is perhaps the cornerstone of advertising and the jet fuel of consumerism. Glamour is what convinces us we want things we don't want and need things we don't need for just long enough to pull the trigger and buy things we shouldn't buy.

"Subjective" is the operative word when it comes to deliberately harnessing glamour this way, that is as a marketing tool. This is why marketers tailor to segments and demographics. Nevertheless it is possible to see macro trends. The grotesque conspicuous consumption and label-mania of the early 2000s has been, I think, gradually giving way to a more sophisticated sales pitch to more sophisticated consumers. Increasingly, we see companies and individuals selling us the absence of things, selling us on negative space, on minimalism. How do you sell things when consumerism itself is passé? You sell anti-consumerism.

Selling anti-consumerism sounds like a paradox, but it functions more like a cliché. Specifically, it's like calling out a cliché as cliché in order to use the cliché without seeming cliché--which is, of course, not a departure from the use of cliché, but the total mastery of it; the ability to bring an old, tired truism back from the dead. And when powerful things resurrect, they tend to be even more powerful than they were the first time. It's hard to argue with a cliché that doesn't seem cliché.

Calling out consumerism is an almost identically neat trick, as exposing and empathizing with consumers' gripes with consumerism creates stronger bonds of trust and loyalty than even the most ideally-targeted pro-consumption ads can.

Stripping away glamour, it turns out, has a glamour of its own. Marie Kondo's promise of spare spaces and aesthetic organization sells books (I bought one). Six years after Patagonia's "DON'T BUY THIS JACKET" black friday ad in 2011, the brand is more popular than ever (I've bought lots). There is a warm, feel-good comfort to Patagonia's fleeces beyond their soft, recycled pile in the company's commitment to environmentalism and responsible sourcing.

This starts to get near the reason why anti-consumerism is so seductive: it not only offers guilt-free purchasable pathways to the rejection of purchasing, but the ability to broadcast that ethos. In a strange kind of alchemy, material things can become signifiers of distain for materialism. It is now possible to buy something in order to show that you're above buying things. And lucrative to sell them. Just because Patagonia is probably one of the best, most ethical companies out there doesn't mean "DON'T BUY THIS JACKET" isn't clever, glamorous advertising and brand stewardship. They're selling us by selling us they're not selling us. But they're still selling us. It's not a reversal of consumerism, but rather another recursive layer embedding the will to buy where it's harder to see and probably harder to cognitively counter.

Recently my most maximalist friend sent around an article from GQ with a request for advice on developing a minimalist wardrobe. No surprise, the author's decluttering process required $5,800 of new spend, including $990 for a single cashmere sweater and $811 for two pairs of sneakers. This is starting to sound like an indictment of minimalism, which it isn't. I enjoyed Marie Kondo's book, and, as previously hinted, own a small mountain of Patagonia. But in this post-truth era of alternative facts, I think it's important to recognize this trend for what it is and unpack the glamour here all the way down to the uncomfortable truth: that anti-consumerism consumerism is still consumption, that a cliché exposed is still a cliché.

RAPID-PROTOTYPING LIFE

We are all the end-users of our own lives, but what we think we want often turns out to be different from what we actually want. I decided to test a few things before going into the next round of production.

When my husband and I started talking this past summer about going on a "sabbatical" of sorts for a few months I was deep into an ilab project for a client and couldn't help thinking about our potential leave in the language of innovation.

The advantages of rapid prototyping in the context of business and technical innovation are well-documented, the biggest perhaps being the ability to test end-user reaction without the up-front investment to actually create the product or service. What you're creating with a prototype is, essentially, a simulacrum of the product or service--something that seems real, mimicking at least one aspect of the real product or service you'd like to test--but is actually just a shell of the real thing that is faster, cheaper, and easier to produce.

One big challenge with rapid prototyping is that there tends to be an inverse correlation between ease of prototypability and the stakes involved. In general, the bigger the investment the actual product or service will require, the harder it is to get people to try to simulate and test it. It's a lot easier to prototype, say, a digital app than a nuclear power plant, so we're often inclined to prototype the app but just take our best guess on the power plant, even though the consequences of making a bad decision re: the power plant are like to be astronomically harder and more expensive to correct downstream.

I spend a lot of time trying to convince people that it is worth the effort to try and prototype the power plant; that--while you should absolutely prototype the app too--it's actually more important to prototype the power plant; that just because something is hard to prototype does not mean you can't or shouldn't try; that low-fidelity is infinitely better than no-fidelity.

Life--that is, where you live, in terms of city, neighborhood, and apartment/house--seems to have way more in common with the power plant. Decisions tend to be long-term, expensive-to-get-out-of, and difficult to try-before-you-buy--it's something, in short, we should absolutely make the effort to prototype but almost never do. It usually takes years if you want to "try out" a few different cities in any meaningful way. No one lets you live in an apartment for a few weeks before you decide whether you want to rent or buy it (kind of a cool idea though). Decisions are often highly-influenced by glamour--by persuasive cognitive illusion.

We are all the end-users of our own lives, but what we think we want often turns out to be different from what we actually want.

I was excited to try it, to rapid-prototype life before making any kind of long-term decision. My husband and I factored in a few weeks of designated "vacation" time into the sabbatical, but built in three month-long stays. A month is long enough to really "live" somewhere vs. traveling; it's long enough to have days where you want to do precisely nothing and, perhaps more importantly, days where you will have to do things you don't want to do (e.g., laundry, grocery shopping). It's long enough to strip the glamour from a place and see it for what it really is. But it's short enough that, if you see something you really don't like, you don't have to live with it for too long; it's short enough to log these preferences and try to correct them fairly quickly in the next monthly iteration. We spent a month in (1) a rural town - Belfast, Maine, (2) a small-mid-size city - Nice, France, and (3) a non-NYC big city - Paris, France. Simultaneously, we experienced living in (1) a residential neighborhood, (2) an "old city" pseudo-residential neighborhood, and (3) a primarily commercial neighborhood, and (1) a huge house, (2) a studio even smaller than what we had in NYC, and (3) a very spacious one-bedroom apartment.

It was low-fidelity, of course. Life is just different when you don't have a day job, and while I spent a fair amount of time writing, we didn't really even try to control for this. Not working is kind of the point of a sabbatical. We definitely did some touristy things outside of designated vacation time.

But even so, in terms of developing a more informed perspective, a deeper personal understanding of what I want in a city/town, a neighborhood, and an abode, I think the experiment resoundingly supported my ongoing hypothesis that a low-fidelity prototype is way better than no prototype at all. I now know, for instance, that I infinitely prefer having a washing machine but no dryer inside an apartment to having both in a communal space shared by the building. I care more about specific neighborhood than greater city. Light and views matter a lot. Size, less than I would have thought (mess, like work, expands to fill the space you allow it), but it is important to have at least one very comfortable, cozy place.

We're leaving Paris tomorrow, and I have no regrets. I recognize how unusual it is and fortunate we were to be able to do something like this, but for anyone who can, I highly recommend it.

IN WHICH DFW & I EXPLORE CHINESE BEAUTY APP MEITU

The IPO of Chinese "Aspirational Beauty App" Meitu is an irresistible conflux of innovation, glamour, and recursion--straight from the pages of Infinite Jest.

Welcome screens from the Meitu app.

I am not the first to gape at the remarkable prescience of David Foster Wallace's largely standalone conceit on the rise and fall of videophony buried inside Infinite Jest. But with the IPO of Chinese "Aspirational Beauty App" Meitu all over the New York Times and Fortune etc. it was such an irresistible conflux of innovation, glamour, and recursion I couldn't forgo the opportunity to explore it a little bit.

If you cobble together some extracts from the Meitu IPO coverage vs. Infinite Jest, it's almost impossible to discern fact from fiction, which is, of course, the purpose of the app itself. Try identifying the sources of these four quotations: Meitu, a (1)"High-def mask-entrepreneur," (2)"allows users to aggressively retouch their faces in photos," for (3)"aesthetic enhancement--stronger chins, smaller eye-bags, air-brushed scars and wrinkles." (4)"A touch can taper your jaw. It can slim your cheeks. Widen your eyes. Of course, it can make you thinner." It runs together seamlessly, but only (2) and (4) are from the news (Fortune and the NYT respectively). (1) and (3) are from Infinite Jest, published in 1996.

Obviously I had to download Meitu and try it. (Is the app's name intentionally an English homonym for "me too"?)

"Get ready for a new you!" the first screen instructs, followed by, in what seems to me a more foreboding admonition than intended, "Get ready for hundreds of emotions!" I found the original color version of my LinkedIn photo, which I consider to be, you know, a pretty good photo of myself, uploaded it to the app, and started tinkering.

Original photo (left) and Meitu-ized version (right)

There was something almost apotheotic about the ability to make pores evaporate, slim down my face, and up the ratio of eyes-to-nose. The whole process took about 30 seconds. It was terrifying, but mesmerizingly so, even if I found the results strange and alien-like--the aesthetics, by default, lean small-woodland-creature. I couldn't help but wonder, if the tweaks were geared toward American beauty standards rather than Chinese, if I would have felt differently. Per the NYT article, this is very much in the works--and will be more or less automated via geolocation usage algorithms. I shudder with "videophonic stress" and vanity--not hundreds of emotions, only two--just thinking about it, about expectations moving from Kim Kardashian to Bambi.

Meitu can "reject[] the idea that its business model relies on people’s insecurities or cultural pressures" and insist "It’s about making you happy," but I don't buy it. In the most flattering light I can muster, it's about getting caught up in DFW's "storm of entrepreneurial sci-fi-tech enthusiasm." Without a filter, of course, it's about Meitu making $$$. Precisely, $629M in the Hong Kong IPO this week and a $4.6B valuation. If DFW's clairvoyance holds, it will be a short-lived boom. Meitu already fell short its target $5B valuation, per the Wall Street Journal. "The question is whether the world wants Meitu’s idea of beauty," the NYT notes. But when innovations are rejected and their markets collapse, there can still be sticky effects:

"Even then, of course, the bulk of U.S. consumers remained verifiably reluctant to leave home and teleputer and to interface personally, though this phenomenon’s endurance can’t be attributed to the videophony-fad per se, and anyway the new panagoraphobia served to open huge new entrepreneurial teleputerized markets for home-shopping and -delivery, and didn’t cause much industry concern."

As a business and innovation strategy consultant, I'm no luddite and have few objections to companies making money. Personally, I also love a good Instagram filter. But Meitu just feels different; using it, I'd crossed one of those invisible lines that you know when you see. I deleted the app immediately.